Nicolai Dmitrievich Kisseleff (1802 – 1869), Russian ambassador

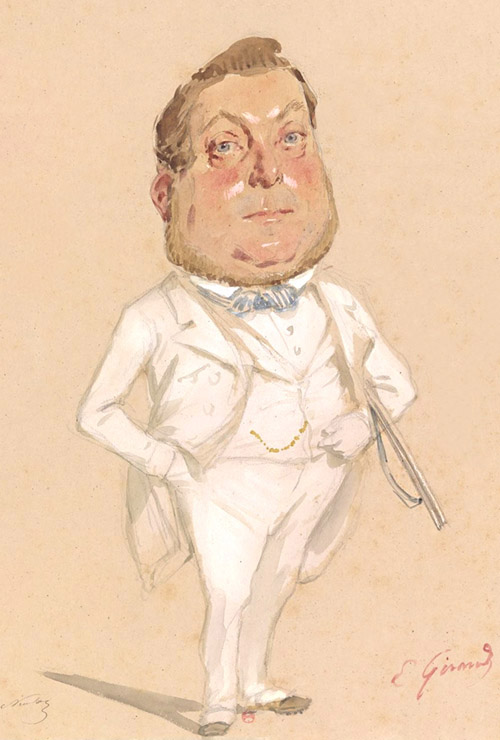

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: atelier 'ND' (c.1854); 3rd: atelier 'ND' (c.1850); 4th: caricature 'Nicolai' drawn by Giraud (1851); 5th: by Chalon (1838).

Written as Kisseleff in French (in Dayot’s gravure from 1900), but also as Kiselev, Kiselyov (the most accurate translation) and Kislew, this aristocrat eluded my research for a long time. Nicolai Kisseleff (Nicolaï / Nicolas / Nikolai) served in the Russian embassy in Paris from 1829 to 1854, with a three-year intermission in London, as secretary (under Pozzo di Borgo) to the plenipotentiary minister.

The education of Nicolai Kisseleff, son of an ancient Russian aristocratic family, was supervised by his eldest brother Pavel Kisseleff, already a statesman at the time.

Nicolai studied French, Italian, Latin, and Greek at Dorpat Imperial University and at Saint Petersburg, along with philosophy, and developed a deep appreciation for music and painting.

During his study in Saint Petersburg, he befriended the poet and playwright Alexander Pushkin. Both men fell in love with the same girl, Annette Olenina, who confessed that she found Nicolai very charming and handsome, even though he wasn't considered big game. Despite her willingness to marry him, Nicolai remained indecisive, allowing his friend Pushkin to propose first.

Leveraging his family connections, Nicolai secured a position as third secretary at the Russian embassy in Paris and left Saint Petersburg in June 1828.

For the next twenty-five years, Nicolai lived in Paris, fully immersed in its vibrant social life. Unmarried and known as a Don Juan and a heartbreaker, he attended concerts, grand balls, and soirées at the Tuileries, including de Nieuwerkerke's16 vendredi-soirées.

He regularly dined with Prosper Mérimée54, positioned next to him in the painting, and other aristocrats.

Julie Bonaparte, daughter of Napoleon’s nephew Charles-Lucien, knew Nicolai since she was seventeen. She immediately liked him when he asked one of the elder ladies at an event: “Who is this little girl who speaks like a woman?” In her memoirs, she writes: “[Kisseleff] is very cheerful and amiable; he has an excessive and very good taste for the arts; he is someone I always enjoy meeting and I relish our conversations.”

During the monarchy, Nicolai worked to limit France’s support for Polish nationalists. Under the Second Empire, he sought to keep France out of Russia's conflict with the Ottoman Empire but was ultimately unsuccessful.

Early January 1854, at a grand-ball organized by Princess Mathilde, Nicolai danced with empress Eugénie as demonstration of the French-Russian bond. Despite his tact, diplomatic ties with Russia were severed later that month, and he left for Germany shortly thereafter. After the Crimean War, he was replaced by his elder brother Pavel.

Nicolai was so devoted to his Conservatoire concert subscription that he sued to reinstate it when it was invalidated during his absence.

A French court ruled in his favor due to force majeure. While the French army conquered Sebastopol, the Russian ambassador reconquered his seat at the Conservatoire.

To his dismay and that of Parisian society, he was barred from returning after the war and posted to Rome in 1855 as ambassador. His 1862 engagement in Rome to Francesca Ruspoli, widow of poet Giovanni Torloni, strained relations with the Pope due to the Council of Trent’s rulings.

Denied a marriage in Rome, and Paris, they wed in Basel in December 1863. The Pope sought to replace him, but the Czar, moved by their love, refused, reinstating Nicolai with an increased salary.

Nicolai continued as ambassador from Florence until his death in December 1869 from a blood infection.

Note: Giraud11 caricatured a ‘Nicolaï’ in a posh white suit. An investigation into de Nicolai family name (marquesses the Goussainville) revealed that none of them had the proper age for Giraud’s caricature, from which I conclude that the depicted person is Nicolai de Kisseleff.