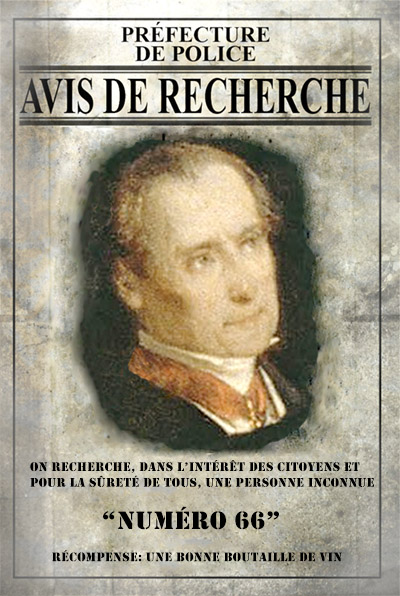

Charles Joseph Barthélémy Giraud (1802 – 1881), Minister of Education

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: by Robert (c.1851); 3rd: by Nadar (1865); 4th: by Reutlinger (1870).

Charles Giraud, a member of the Institute since 1842, likely attended a Louvre vendredi-soirée during his brief tenure as Minister of Education in 1851, or his appointment to the State Council in 1852.

This eminent lawyer, historian, and professor, distinguished by the cravate rouge of a Commander of the Legion of Honor (1847), secured a place of prominence —unlike his namesake, the painter Giraud47.

Identifying Minister Giraud proved challenging. Dayot’s gravure (1900) mentions “Ch. Giraud”, but not at the correct position for either the Minister or the painter. In 2016, he remained the only person in the painting that I had not identified. With kind assistance from the Bibliothèque nationale de France and by going though their list of 8,000 Commanders, my forensic analysis ultimately confirmed his identity.

Rather than attending the political-artistic men-only vendredi-soirées at the Louvre, Giraud preferred the intellectual salons hosted by Institute members. His companions included his best friends Thiers, Mignet, Mérimée54 (seated nearby), and Princess Julie Bonaparte, Marquise of Roccagiovine and cousin of Princess Mathilde. A professor and bibliophile, Giraud excelled in disseminating and discussing diverse subjects with great eloquence.

Born near Aix-en-Provence, Giraud studied and became a professor of law in his native region. His younger brother Louis became known for creating the Carpentras Canal. In 1831, Charles married Marie Julian (aged 16), with whom he had two children: Joseph, a banker, and Claire, who wed historian Eugène Rozière in 1850. Upon joining the Institute in 1842, the family had to relocate to Paris.

Despite holding numerous positions —including minister, professor, historian, education inspector, and law inspector— Giraud struggled financially due to his costly bibliophile pursuits. He confided in colleagues that he was engaged in a fool’s job. His strained finances contributed to the deterioration of his marriage.

In March 1855, Marie requested a legal separation, and in July, she appealed to Minister Fortoul46 for assistance in reducing Giraud’s debt of 500,000 francs. Supported by de Nieuwerkerke16, but to his great regret, Giraud sold 3,304 items from his library, including a thirteenth-century Bible and first editions of Molière’s works. This sale covered one-third of his debt. Nevertheless, the couple formally separated in October 1855.

By this time, Giraud attended the literary salons hosted by Princess Julie, on Friday-evenings in parallel with the soirées at the Louvre. Her diary reveals they met twice weekly and, in her absence, he wrote her affectionate letters. She writes: “His cheerful and amiable character pleases me infinitely,” adding: “He is loyal and discrete.”

Giraud introduced Mérimée to her and Princess Mathilde. Julie reciprocated by introducing Giraud and Thiers to Malvina d’Albufera (student of Charles Müller18), who entered a well-hidden relationship with Thiers.

Released from several professional obligations in 1868, Giraud dedicated himself to teaching and writing. Over the final phase of his life, he authored over 200 books. His extensive knowledge allowed him to correspond with Ingres and de Nieuwerkerke regarding the reorganization of Beaux-Arts schools, as well as produce works like Charles Perrault’s Mother Goose tales (1864) and complex studies on Roman law.

After months of illness, Giraud died on December 13, 1881. He was interred in the family tomb at Pernes-les-Fontaines. Among his lasting contributions as Minister of Education was the initiation of a telescope at the Paris Observatory.