Overview of Sources, Press Commentary, and Historical Reference Materials

Click images above to access other main pages. Click Une Soirée or outside this page for the interactive image.

For my initial identification and contextual profiling of the individuals portrayed in Une Soirée, I conducted, between mid-2015 and early 2017, over 500,000 search queries.

These efforts yielded approximately 8,000 pertinent references. The scope and quantity of material consulted far exceed what could feasibly be compiled into a conventional reference list.

Nevertheless, to ensure transparency and traceability, I archived all search records —each indexed by keyword, URL, date, and time— enabling retrospective retrieval and verification.

A cornerstone of this research was the Gallica database of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), an expansive and continuously evolving digital repository considered among the finest globally —arguably surpassed only by Google’s commercial archives. For scholars, Gallica is an ideal resource. Beyond material directly relevant to the painting, its subjects, the soirées, and the Second Empire, it furnished invaluable peripheral information, including early photographic documentation of an earthquake in my hometown in Italy, the socio-culinary evolution of the baguette, and weekly scientific reports from the Académie française on topics ranging from chemistry to oncology. These findings reaffirmed the scientific rigor already present two centuries ago.

The dedicated BnF archives also encompass most of the caricatures produced by Eugène Giraud, several of which proved instrumental in verifying identities within the painting. The BnF staff also kindly granted access to supplementary documents and artworks not available in the public domain.

Primary source material regarding the vendredi-soirées was drawn from a wide range of Parisian newspapers, including Le Ménestrel, Le Nouvelliste, Le Pays, Le Charivari, L’Artiste, Le Courrier Français, Le Figaro, La Lumière, Gazette Musicale, Le Corsaire, Journal des Débats Politiques et Littéraires, Le Constitutionnel, Revue des Beaux-Arts, Le Petit Courrier des Dames, Le Daguerréotype, Vert-Vert, as well as international publications such as Galignani’s Messenger and L’Indépendance belge. Multiple years’ worth of editions were reviewed for each title.

The Annuaires or annual almanacs also proved invaluable, particularly for governmental and imperial references. While some volumes were already text-searchable, others required customized OCR (optical character recognition) processing to render them accessible.

The temporal range of my research spanned from the 1820s to the 21st century.

Complementing the French and English materials, I extended my investigation to German, Dutch, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese archives. Some of these resources remain inaccessible to the general public and/or are available only via subscription-based access.

In addition, I compiled an extensive library of books and theses, both printed and digital, across multiple languages. These ranged from a first edition of Dayot’s Second Empire (1900) to unpublished primary sources such as the diary of Princess Julie Bonaparte, as well as the memoirs of Viel-Castel, Chennevières, and the Goncourt brothers.

Several press documents proved especially significant in shedding light on the soirées, the painting, and their participants:

- Le Constitutionnel, 22 January 1854

Conservator Horace de Viel-Castel authored a detailed and favorable article outlining the purpose of the soirées and the nature of the invited guests. - Le Nouvelliste, 9 May 1854

This daily paper published a first impression of the unfinished painting, providing a description that markedly diverges from the final version. The article was reprinted in Le Nouvelliste on 11 May 1854. A more expansive version appeared in Le Petit Courrier des Dames on Saturday, 27 May 1854. Internal evidence suggests that the text was authored by Amédée de Taverne and offered to multiple outlets: Le Nouvelliste was first to publish it, followed by a shortened version in Le Ménestrel (14 May), and finally the original text appeared—albeit belatedly due to limited column space—in Le Petit Courrier. The article was subsequently copied in various French and English newspapers.

Each version of the article includes the following excerpt:

"Initially, the artist had created a scene in which Mlle Rachel recites verses. This idea has since been altered—the famous tragedian will not appear in the painting."

This revision may partly explain the critical disappointment surrounding the final composition, which ultimately failed to achieve de Nieuwerkerke’s vision of a commemorative tableau for his vendredi-soirées.

A technical analysis of the painting—preferably involving X-ray imaging—may help clarify this decision and reveal prior compositional elements.

For additional documentation, see the detailed article in Le Petit Courrier des Dames.

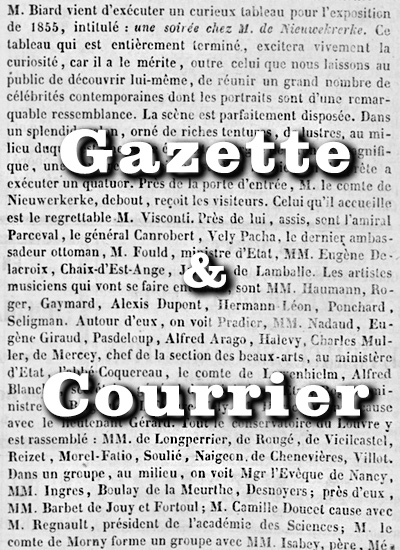

Gazette du Midi (March 12, 1855) & Courrier de l’Aude (March 14, 1855)

These two regional newspapers were integrated into my research archive on April 21, 2024—nine years after the original analysis. They include names not previously documented and offer potentially valuable insights into Une Soirée au Louvre. While the Courrier corrects a few of the Gazette’s misspellings, both preserve the same inaccurate claim: a total of 75 persons represented.

Notably, these publications introduce names that were never mentioned in the contemporary Parisian press and remain unsupported by subsequent historical research. Even so, their inclusion warranted analysis. The content appears to derive from an oral account of the painting, likely provided by someone only partially familiar with its composition, and recorded by someone unfamiliar with the individuals named.

Considering conflicting or insufficient evidence, several suggestions were ultimately set aside. Their validity may yet be confirmed by further discoveries —ideally from Parisian sources. Where credible, I have retained plausible candidates and, in instances of competing identifications, enabled the reader to consider alternative attributions.

Details of this evaluation are available on my Gazette du Midi Analysis page.

Souvenirs d’un directeur – Philippe de Chennevières (1883)

This memoir offers a wide-ranging overview of museum conservation practices in 19th-century France and contains several references to individuals featured in Une Soirée au Louvre.

Memoirs of Count Horace de Viel-Castel (1883)

Spanning six volumes and nearly 2,000 pages, these posthumously published diaries present a vivid, often biting perspective on the Second Empire. Viel-Castel reflects on the art world, politics, finance, and society from 1851 to 1864. Published in Switzerland after his death to avoid censorship and retaliation from those named, the memoirs caused considerable scandal and fueled debate for years.

Viel-Castel references more than fifty individuals depicted in the painting. He frequently includes the dates of their caricatures by Eugène Giraud, details of musical performances at the soirées, and a wealth of anecdotes—some notably irreverent. I devoted an entire month to analyzing his writings and identified over 1,800 references to persons either present in, or closely associated with, Une Soirée au Louvre.

Le Second Empire – Armand Dayot (1900, p.105)

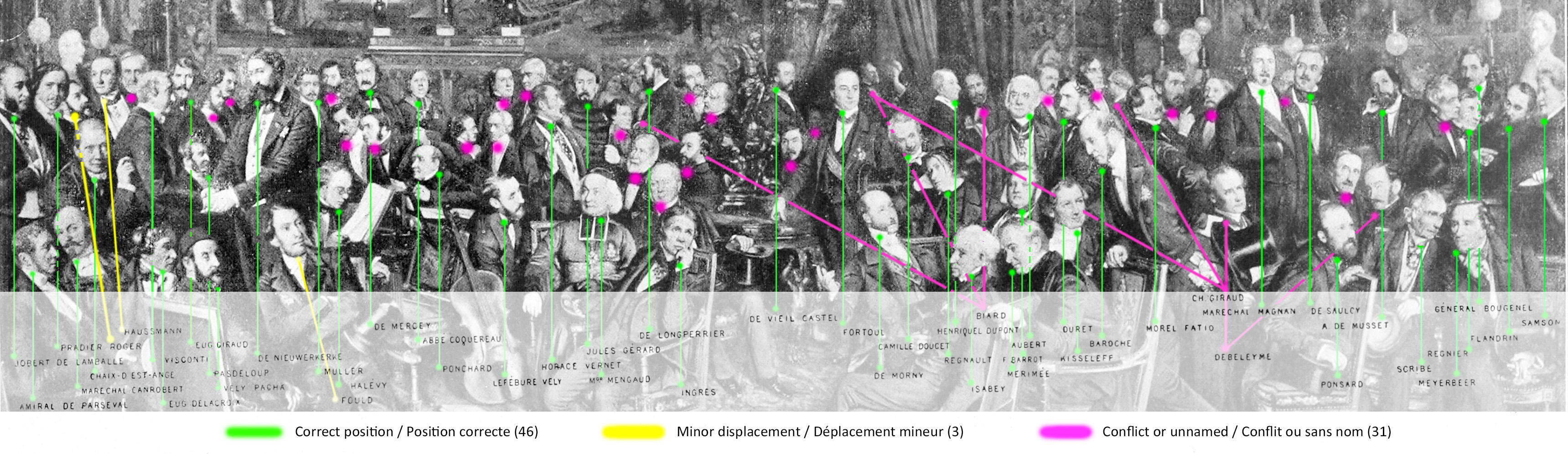

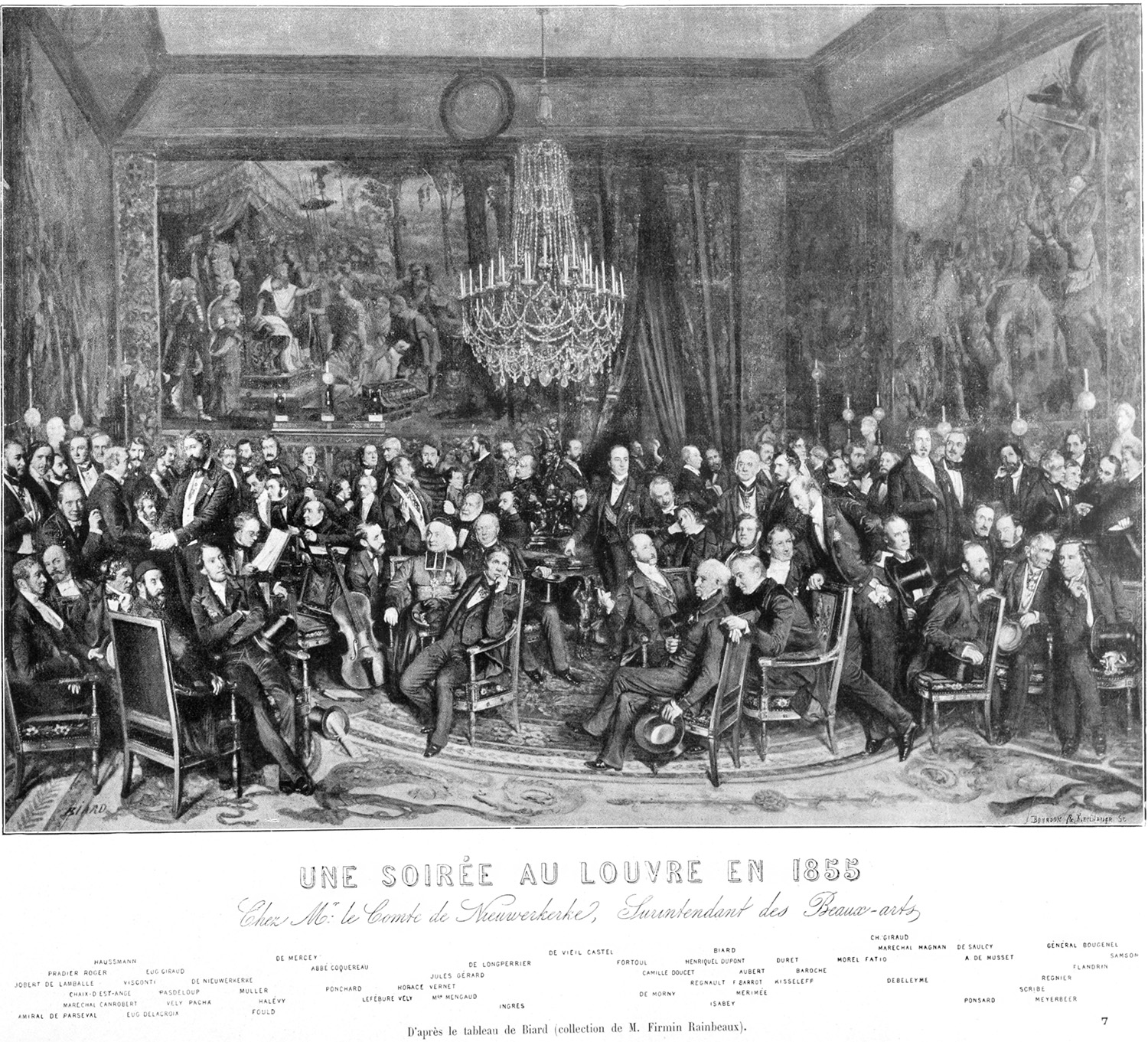

As an inspector of the Beaux-Arts and an esteemed critic, Armand Dayot published an illustrated overview of the Second Empire featuring many participants of the vendredi-soirées. It includes the only known engraving of Une Soirée au Louvre, annotated with fifty-one names.

After the disastrous reviews from the critics at the 1855 Salon, the painting was placed in de Nieuwerkerke’s private Louvre apartment. Upon de Nieuwerkerke's retirement to Italy in 1872, the painting was moved to the reserve collection of the Louvre. In 1881, its custodial rights were transferred to empress Eugénie.

Dayot’s engraving was produced with assistance from Eugénie's representative Firmin Rainbeaux, who had researched the imperial collections for over three decades. The names are rendered in sans-serif type —a style developed in England in 1816 but only broadly used for titles by the late 19th century.

The absence of a complete reference list suggests that those annotating the image may not have identified all figures with certainty, potentially relying on hearsay.

This stands in marked contrast to the 1854 Panthéon by Nadar, which meticulously lists all 249 individuals (in serif type).

Using this as a foundation, I preserved all names from the engraving and confirmed their placements —only diverging from the documented positions when substantiated evidence warranted a correction.

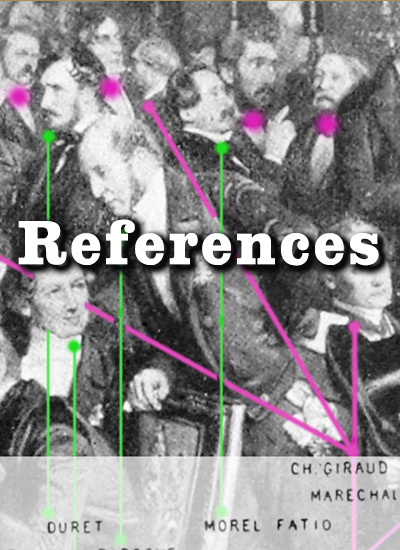

Besides three minor name placement errors (for Roger04a, Haussmann07, Fould17) there are three unclear placements (Biard, Ch. Giraud, de Belleyme), that I discuss in their profile pages (see also image below). It remains unclear why Firmin Rainbeaux wasn't able to identify more of these 80 persons, including well-known ones like Chennevières20, Rousseau64, Reiset65, and Eugène Isabey75.

Eugène Giraud’s Caricatures

Currently, 179 caricatures by Eugène Giraud have been documented in public collections, although the complete series is estimated to include around 220. It is hoped that additional works will surface.

A detailed survey by Lemoisne in the 1920 issue of the Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art Français catalogs all known caricatures at the time and includes invaluable information on the hundreds of guests who attended the soirées.

Soirée au Louvre Research Archive

The database I have assembled now comprises approximately 60 GB of material across 17,000 files. To manage this data, I had to install a dedicated local search engine. With over 90 individuals linked to the painting and more than 4,000 interconnections, the structure is designed to support a scalable mathematical model (d3.js-based) in future iterations.

By tracking all my searches, all findings can be retrieved, except when data has been lost by altered or discontinued internet sites. Nevertheless, should you have questions about any of the items on this site, feel free to let me know.

Updated: 2025-09-22