Alfred de Musset (1810 – 1857), poet, writer, dramatist, critic

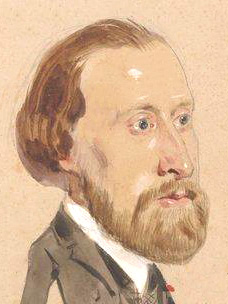

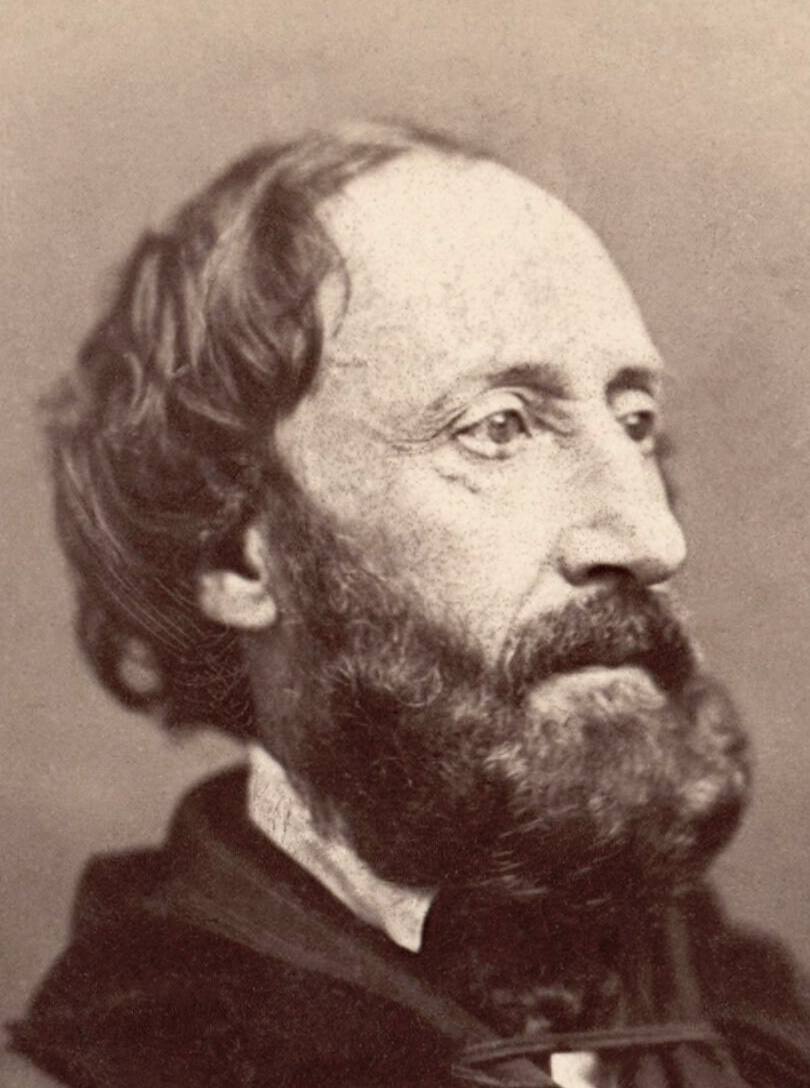

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: Landelle (pastel, 1854; 3rd: caricature by Giraud (1852); 4th: Gavarni (1854); 5th: photo by Nadar (c. 1855). Video: Ballade à la lune song by Brassens

Louis-Charles-Alfred de Musset, one of the foremost figures of French Romanticism, first attended the Louvre’s vendredi-soirées on 7 February 1851, where he recited his poem L’Andalouse. He returned on 5 March 1852, an occasion on which Eugène Giraud11 likely caricatured him, and again on 17 March 1854. He may have attended more often, accompanying his muse, the tragedienne Rachel Félix81. She was both a source of inspiration and a romantic partner. De Musset attended her performances and published favorable critiques in the Revue des Deux Mondes.

In 1852, Rachel sent him a note regarding his absence from her performance on March 19 :

“Dear Poet,

You so skillfully avoid people who presume to recite your verses that I want to congratulate you twice. Yesterday you did not come to the Louvre; this morning you had me hand over your card without wanting to wait for me any longer. What does that mean? […]”

De Musset replied promptly, taking advantage of the frequent postal deliveries of the time:

“Dear Muse,

I was unable to go to the Louvre, much to my regret, but I spent a good fifteen minutes yesterday morning in your courtyard, ‘blowing into my fingers,’ as Racine said.

Please believe, I beg you, that I am still entirely yours, and that whoever interprets their thoughts can no more complain about it than about the crucible that refines gold. A thousand best wishes […]”

When Une Soirée was exhibited at the 1855 Salon, critic Edmond About wrote:

“This painter is incapable of painting a gentleman… […] The Salon of Mr. Niewerkerke is full of witty figures that Mr. Biard has uniformly vulgarized by subjecting them to the same smile and the same physiognomy. See what he has done with the charming head of Mr. Alfred de Musset…”

Yet, in light of de Musset’s physical decline, Francois Biard’s36 portrayal may be considered generous. Decades of depression, alcohol and opium use, and syphilis, contracted during visits to brothels in the late 1820s, had aged the once-dashing poet prematurely, as evidenced by Nadar’s photograph (above) from 1855 or 1856.

De Musset’s most celebrated works —his Nuit poems (e.g., La Nuit d’avril), satirical plays, and short novels such as Les Caprices de Marianne, Lorenzaccio, and On ne badine pas avec l’amour— were composed in the 1830s. His health declined in the following decade, and his literary output diminished. By the time of his first Louvre soirée in 1851, his contributions were minimal. In 1852, Minister Achille Fould17 granted him a lifelong post at the Paris Library to support him during his illness. Despite his physical deterioration, de Musset retained his wit and intellectual brilliance until near the end of his life.

A revealing self-reflection appears in a short poem he wrote in early 1855, commenting on his portraits:

Nadar, in a sketched profile, has rendered me in vain;

Lendelle, drew me asleep, and also half;

Biard, rendered me awake, but also half;

Giraud alone, with a quick and fearless stroke,

For love of truth, without disguise, made me look unwise,

What egg will Gavarni lay in this nest someday?

Lendelle’s drawing, depicting a youthful de Musset, was the most widely recognized. Gavarni’s engraving appeared only after de Musset’s death. The publication of this poem in 1891 rekindled scholarly interest in Une Soirée au Louvre. It was not until Dayot’s 1900 monograph and subsequent research that the painting’s existence was confirmed in 1926.

Beyond his literary achievements, de Musset is remembered for his tumultuous relationship with George Sand, which lasted intermittently from 1833 to 1835. The couple frequented Parisian bars and salons, often in the company of artists such as Delacroix10, Hugo, Pradier03, Mérimée54, and Sainte-Beuve.

In the summer of 1833, a spirited late-night discussion on French erotic literature, perhaps fueled by absinthe, his “green muse,” led to their collaboration on Gamiani, ou une nuit d’excès, a highly salacious novella published under the pseudonym Alcide, baron de M***. Though initially circulated privately, one copy reached the press, and their authorship was only acknowledged years later.

Their ill-fated “honeymoon” in Venice during the winter of 1833 inspired de Musset’s semi-autobiographical novel La Confession d’un enfant du siècle (1836). He later summarized their incompatibility with characteristic irony: “I worked all day; in the evening, I wrote ten verses and drank a bottle of brandy; she drank two liters of milk and wrote half a novel.”

In 1839, de Musset pursued the young singer Pauline Garcia (1821 – 1910), a protégé of Liszt50b, attending her performances and writing admiring reviews. However, besides being discouraged by George Sand, it was de Musset’s physical appearance —yellowed fingers, lips, and teeth from excessive smoking— that dissuaded her. Pauline later married Ary Scheffer’s41a best friend Louis Viardot. Her second daughter is rumored to be fathered by Gounod70b.

Shortly before his death, de Musset confided to his friend Horace de Viel-Castel43 his sorrow at not being able to bid farewell to his “friends” Raphael, Giorgione, and Leonardo da Vinci at the Louvre. Moved by this sentiment, Count de Nieuwerkerke16 arranged a torchlit visit.

While de Nieuwerkerke dined with Viel-Castel and Arsène Houssaye, de Musset wandered the museum’s halls alone, offering a final salute to the Mona Lisa and La Fornarina. Upon returning, pale and tearful, he thanked his host:

“It is clear, my dear Nieuwerkerke, that you were born a great artist and a great lord.

It was the first time that a poet was treated as a sovereign.”