Rachel Félix (1821–1858), Tragédienne

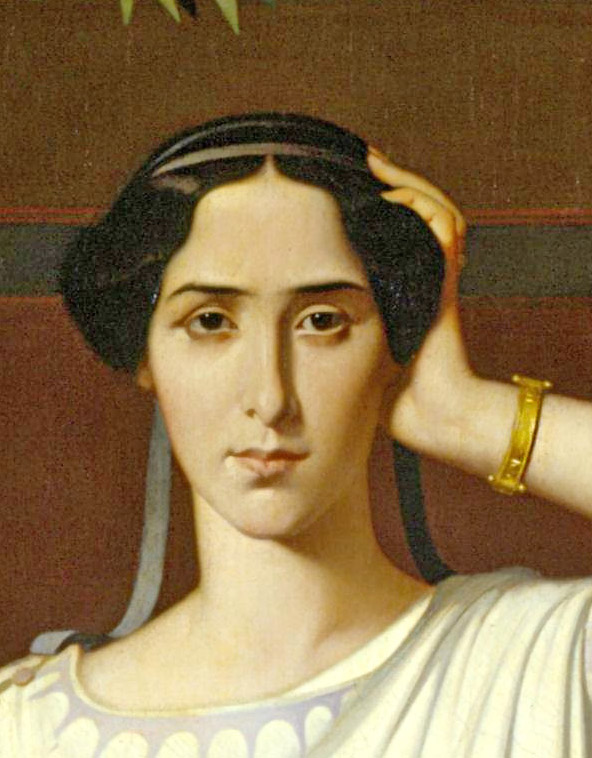

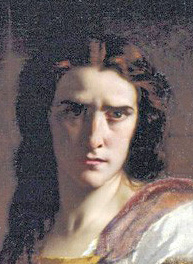

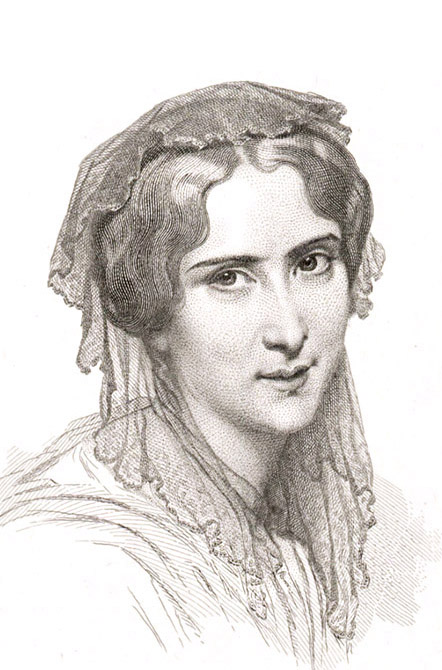

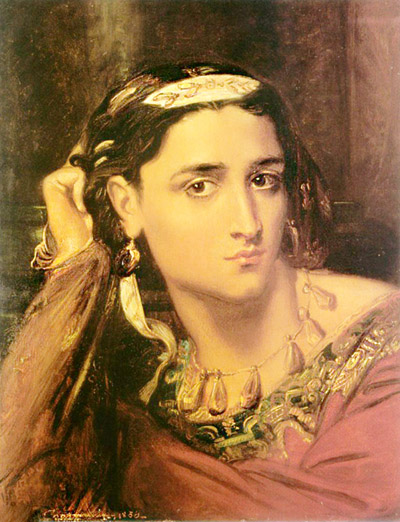

1st image: Soirée (version 1853); 2nd: Amaury Duval (1854); 3rd: Ingres (restored newsprint, c.1856); 4th: as Phedre, by Delacroix (1840s); 5th: in Macbeth, by Müller (1849); 6th: engraving by Henriquel-Dupont (1852).

Elisabeth Rachel Félix, known simply as Rachel, was intended to appear as the central figure in Une Soirée au Louvre. Her removal from the composition in early 1854 profoundly altered the painting’s internal logic: visual lines of attention now terminate abruptly, and several male figures, initially oriented toward her, were repositioned, leaving gaps in the narrative structure.

Rachel and the vendredi-soirées

From the earliest weeks of de Nieuwerkerke’s16 vendredi-soirées, Rachel’s presence and performances generated excitement among attendees.

On 7 June 1850, de Nieuwerkerke personally escorted her into his salon, where she performed a scene from Racine’s Phèdre, an interpretation that contemporary critics described as having an “inconceivable” impact on the assembled audience.

She returned on 21 June to recite prose by the seventeenth-century bishop Bossuet, possibly supplementing it with an excerpt from her role as Lydie in Ponsard’s70a Horace et Lydie.

On 5 March 1852, she again captivated the male audience by reciting stanzas from Alfred de Musset’s73 ode to the singer Maria Malibran, during an evening that also featured the celebrated pianist Sigismond Thalberg.

The absence of a caricature of Rachel by Eugène Giraud11, as well as the silence of Viel-Castel’s43 journals on this point, strongly suggests that she never remained for the après-soirée gatherings.

Frédérique O'Connell (1853)

Rachel’s appearances at the Louvre soirées quickly acquired a reputation comparable to de Nieuwerkerke’s candlelit après-soirée visits to the Venus de Milo. Her inclusion as the sole woman among eighty men in Une Soirée would have crowned de Nieuwerkerke’s ambition to assemble, impress, and influence the aristocratic elite. Yet circumstances —and her perception by the public— were shifting rapidly.

In April 1854, a journalist —likely Léopold Heugel68, proprietor of Le Ménestrel— visited Biard’s36 studio and published his observations in several newspapers (Le Ménestrel, Le Nouvelliste, Vert-Vert, Le Petit Courrier des Dames). He reported:

“It should be understood that we are only giving indications, since the painting is barely halfway completed. Originally, the artist had imagined the moment when Mlle Rachel would recite some verses. That initial arrangement has been changed. The famous tragedienne will not be depicted in the painting.”

The question thus arises: why was this celebrated figure, whose connections extended to the imperial household, suddenly excluded?

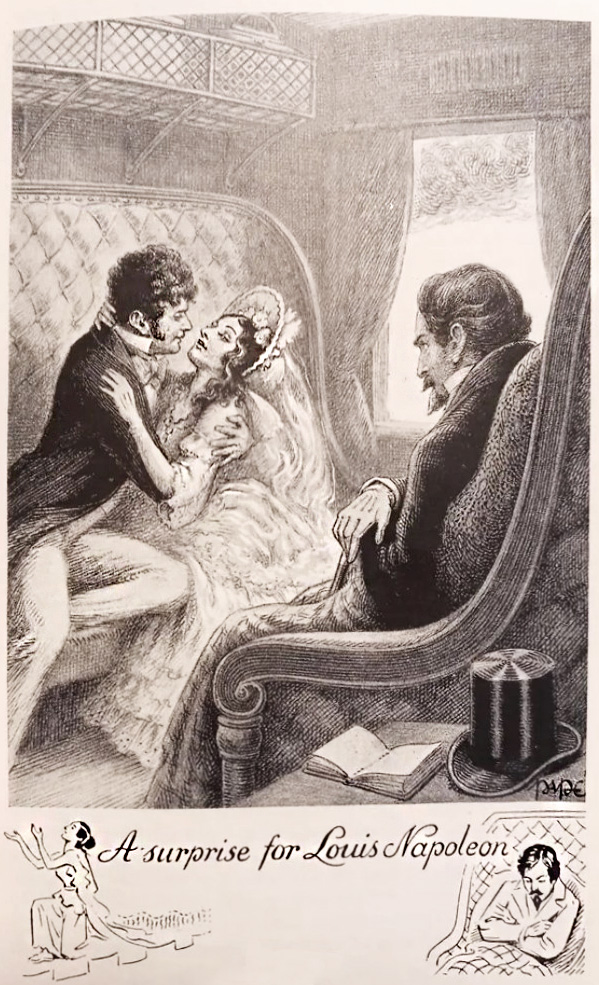

on train to Birmingham (1846)

Since 1842, Rachel had been in a liaison with Count Walewski, son of Napoleon I. Their son Alexandre was born in November 1844 and legally recognized by his father. Walewski appears to have been the man she valued most deeply, yet between 1842 and 1848 she simultaneously maintained an affair with Marshal Arthur Bertrand, another intimate of Napoleon I.

During her London tour in July 1845, she entered into a relationship with the exiled Louis-Napoléon, the future Napoleon III. This liaison resumed during her subsequent London visits in 1846 and 1847, when —pregnant by Bertrand— she also encountered Louis-Napoléon’s cousin, Prince Jérôme Bonaparte (“Plon-Plon”).

When Louis-Napoléon discovered her in an intimate embrace with his cousin on a train, he ended the affair.

Walewski, too, broke with Rachel. When he asked why she had been so unfaithful, she reportedly replied (though the remark remains unverified): “I am what I am. I prefer renters to owners.” Walewski married later that year the Princess di Ricci, who later also became one of the emperor’s mistresses.

Plon-Plon remained devoted to Rachel and even commissioned a small temple for her in 1856, decorated by Ingres39. He later remarked: “You cannot dismiss a woman who deceived you with such grace.”

After Napoleon III’s marriage to Eugénie de Montijo in January 1853, an emperor-funded painting prominently featuring his former mistress, as well as of other members of the Bonaparte family, would inevitably have attracted press scrutiny.

Viel-Castel recounts in his journal how Lucien Bonaparte, Prince de Canino (“one of her lovers who did not have to pay”) thought it charming to send a four-horse carriage in imperial livery to parade her around Longchamp, where the public greeted her thinking she was the Empress. Minister Fould17 was compelled to issue a special imperial decree to halt such displays (“Rachel’s law,” 17 March 1853).

Pressured by her father —who had forced her since childhood to beg and sell oranges in cafés— Rachel continually demanded higher compensation from the Théâtre-Français (the state institution to which the Comédie-Française troupe belonged) and initiated legal action to enforce her claims, while fulfilling only the minimum obligations of her contract.

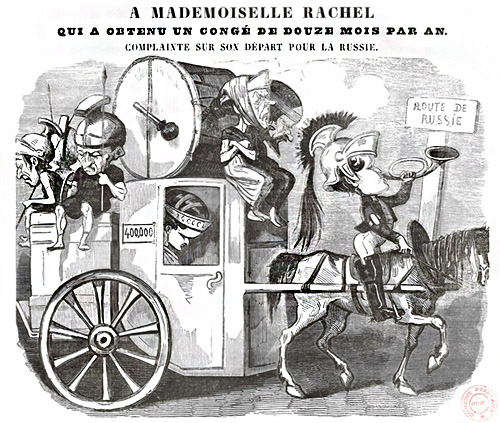

Minister Fould attempted to mitigate the disruption by granting her paid leave for health reasons (she suffered from consumption: tuberculosis). Instead, she made lucrative tours in England, the Netherlands, and Belgium.

In October 1853, Fould authorized a subsidy of 50,000 francs for her Russian tour, both to distance her from Plon-Plon and other Bonaparte associates, and to secure her contractual ties to the Théâtre-Français. When she returned in March 1854, having earned more than 300,000 francs, news of her resignation provoked public outrage. Few knew that she had withdrawn to care for her dying sister Rebecca in Pau; Rebecca died in Eaux-Bonnes on 19 June.

These converging factors ultimately worked against her.

It is plausible that de Morny48, the emperor’s half-brother, Mérimée54, close to empress Eugénie, and/or Princess Mathilde Bonaparte —Plon-Plon’s sister and de Nieuwerkerke's companion— advised de Nieuwerkerke to avoid scandal by excluding from Une Soirée the image of a woman being the mistress of multiple members of the Bonaparte family and who had lost her audience because of her greed.

When the journalist visited Biard’s studio, the painter must have been urgently reconfiguring the composition to compensate for her removal. Close examination of the final canvas reveals several adjustments that were never fully corrected. You can find more details in the Une Soirée History pages.

Despite Rachel’s absence from Une Soirée, many of her admirers, collaborators, and lovers remain present in the painting. At least twenty men depicted had been closely associated with her. Among the most significant was Samson.

Joseph Samson

by Disderi (c.1846)

When Samson first encountered Rachel, she was nearly illiterate, possessed a limited vocabulary, and lacked musical aptitude. What distinguished her from other young aspirants was her extraordinary tenacity and prodigious memory.

After several years of private instruction under Samson, she was deemed ready to apply to the Conservatoire. His examination report famously stated:

“Lacking physical attributes but possessing an admirable theatrical disposition. Definitely to be admitted.”

The relationship between Samson and Rachel can been compared to the Pygmalion myth, later immortalized by Bernard Shaw.

Her mastery of new roles, her diction, gestures, and physical expressiveness, was the product of weeks or months of rigorous training under Samson’s direction. During rehearsals she appeared at his home at all hours, insisted on his presence in her dressing room before every performance, and wrote to him for guidance whenever they were apart. She entered the Societaires of the Comédie-Francaise in 1838.

Despite Samson’s immense investment in her education (her income soon surpassed that of her mentor and platonic companion) their relationship was marked by constant quarrels. Samson deplored what he perceived as her greed and vindictiveness.

The year in which Une Soirée was revised was also the year Rachel severed ties with her tutor. The new roles she undertook thereafter met with little success. Her last performance was a repeat of Adrienne Lecouvreur (Scribe and Legouvé, 1849) during her American tour, performed in Charleston in December 1855.

Rachel’s theatrical ascendancy was also facilitated by the support of ministers Fould and Baroche61. Fould, who oversaw the Théâtre-Français, was responsible for her salary and repeatedly intervened on her behalf. After unsuccessful attempts by de Musset, Augier, and Ponsard, Rachel pressured Baroche in 1849 (by entering his carriage) to appoint her friend Arsène Houssaye as artistic director of the Théâtre-Français.

Legal disputes brought by theatres or individuals, such as Legouvé, seeking compensation for her failure to fulfil contractual obligations were often resolved in her favour by the court president Belleyme66a, who exempted her from penalties.

Several of Rachel’s admirers and lovers appear in Une Soirée.

The sculptor Pradier03 courted her and was frequently admitted to her dressing room. Writers such as Augier53, Ponsard70a, and de Musset73 maintained passionate relationships with her, dedicated works to her, and accompanied her on travels abroad. De Musset had written the favourable review that helped launch her career in 1838.

De Morny48, one of the most influential figures of the Second Empire, also pursued Rachel and was a frequent visitor backstage. Despite their vastly different social origins, Rachel and de Morny shared notable traits: she was the grande dame of the theatre, he the grand seigneur of the regime. Both were marked by ambition, strategic acumen, a taste for wealth, a succession of affairs, and a pronounced self-interest.

Other men depicted in Une Soirée were professionally linked to Rachel: Scribe74 wrote plays expressly for her; Régnier77 collaborated with her on stage; the tenors Roger04a and Nadaud14 performed at her gatherings; and painters such as Müller18, Ingres39, and Duval44a produced portraits of her, several of which became known to the public thanks to their engravings by Henriquel-Dupont51.

Notably absent from the painting are Arsène Houssaye —surprising given his close friendship with de Nieuwerkerke and Rachel— and the publisher Michel Lévy (who owned newspapers Vert-Vert and le Nouvelliste), who was deeply devoted to Rachel and cared for her during her final years.

Rachel (1853)

Rachel’s health deteriorated rapidly.

Travels to Egypt in 1856 and 1857, undertaken in search of a warmer climate, brought no improvement. She returned to France in June 1857 and stayed near Montpellier, where Houssaye and Ponsard visited her.

Her final journey took place in early 1858 aboard Prince Napoléon’s yacht, from Marseille to Le Cannet.

She died there, at the Villa Sardou, at the age of thirty-six.

The former beggar girl left her family an inheritance estimated at 1.2 million francs.

A successful medication for tuberculosis was only invented 75 years later.

I’ve created a conceptual reconstruction of Une Soirée —as it may originally have been conceived in 1853— based on a photograph by Villeneuve in 1853, in a costume resembling that worn for her performances as Phèdre. You will access the 1853 version of Une Soirée by clicking outside this page, or on the top left image.