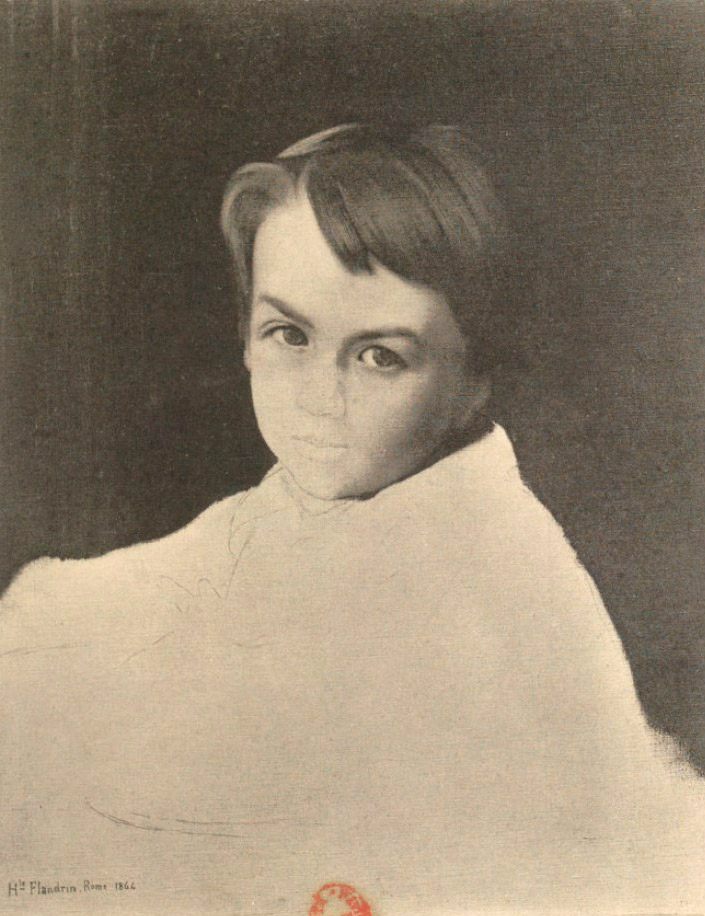

Hippolyte Flandrin (1809 – 1864), painter

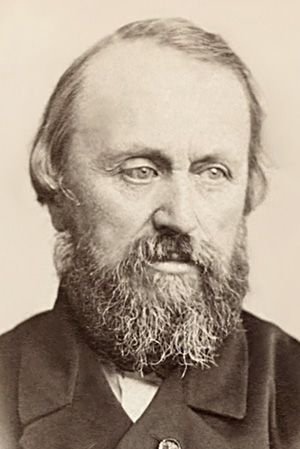

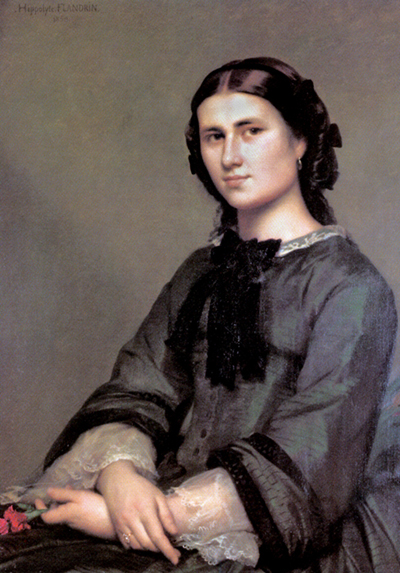

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: photo Daguerre (1848); 3rd: autoportrait (1853); 4th: Ingres39 (1855); 5th: Heim28b (1856); 6th: photo Reutlinger (1860). Note: Daguerre photo 2 reversed to match hairline & eyes.

Note: Flandrin’s placement in three-quarter view makes it almost certain that he did not pose for the portrait and that Biard36 relied on engraved sources. From birth, Flandrin had a strabismus (“squint”) of the right eye; after an unsuccessful operation in 1841 the deviation worsened. Nearly all his self-portraits, double portraits with his brother Paul, and photographs represent him either in profile (obscuring his right eye, as in image 3) or with his right cheek toward the viewer.

Amid the worldly aristocrats in Une Soirée preoccupied with entertainments, politics, and courtesans stands the intense and deeply religious painter Jean Hippolyte Flandrin.

Flandrin felt uneasy at soirées such as those hosted by count de Nieuwerkerke16. More than once he noted in his letters that he was ill at ease about his clothes (wearing a casquette) and manners. He wears the rosette of Officer of the Légion d’honneur, awarded on 12 August 1853 in recognition of his murals at the church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul.

Supported by Ingres and other friends, he was elected the following day to the Académie des Beaux-Arts, receiving six times more votes than candidate Delacroix10, who would wait another four years for the same honor.

These distinctions account for Flandrin’s fame and presence at a vendredi-soirée. He likely attended soon after the soirées reopened that year on December 9; the conservator Viel-Castel43 reported his attendance in Le Constitutionnel on January 22,1854.

Flandrin was one of the prize winners of the Prix de Rome (besides Ingres, others represented in Une Soirée include Pradier03, Duban60, and Gounod70b), which afforded him five years’ residence in Rome (1833–1838), initially under Horace Vernet31 and, from 1835, under Ingres. Despite frequent illnesses and failing eyesight, he cherished Rome’s cultural environment and inspired fellow artists by his passion and sincerity.

with baron Armand Mackay (May 17, 1858)

On returning to Paris —with frequent visits to his native Lyon, where he also exhibited at the Salons— commissions came quickly, notably after his vivid portrait of Madame Oudiné (1840), which earned him “ten times more attention than last year.”

His portrait of Cécile Delessert (later comtesse de Nadaillac) in 1842 brought 3,000 francs and, through Cécile’s proximity to Eugénie de Montijo (the future Empress), substantially expanded his clientele. Flandrin’s portraits of beautiful women share much with those by Amaury-Duval44a, another pupil of Ingres; the decisive difference is that Flandrin knew how to market and place them effectively.

Flandrin's portrait of Chaix d’Est-Ange06 in 1845, so large that it had to be brought in through the roof, marked his final advance to fame. In 1847 he wrote to his brother Paul: “As for orders, I am overwhelmed. If only I had ten arms!”

Baudelaire offered a dissenting view: “[He] failed in the portrait of M. Chaix-d’Est-Ange. It is merely the semblance of serious painting; it does not seize the well-known character of this refined, biting, ironic figure. It is heavy and dull.”

By that time Flandrin had already completed murals for the church of Saint-Paul in Nîmes (recently severely damaged by rain) and for Saint-Germain-des-Prés (1846) in Paris. His work at Saint-Vincent-de-Paul in Paris, commissioned during the Haussmann07 period, began in 1849 and lasted four years.

Hippolyte and his brother Paul were very close and exchanged letters frequently when apart. As early as 1857, Hippolyte advised Paul to “let yourself go, to surrender to your impressions, to paint more as you feel than as you see.” It would be many years before the term “impression” appeared in French critical discourse in relation to Monet and Renoir. Despite his brother’s encouragement, Paul remained faithful to the tradition he had learned as a pupil of Ingres and continued to paint historical landscapes.

In 1860 Flandrin reported that he had already refused 150 commissions; after completing a life-size portrait of Emperor Napoleon III he had even less time to spare.

unfinished work (1864)

In addition to a second attendance at a vendredi-soirée on 27 April 1860 (where he avoided caricaturist Eugène Giraud11 who probably was depicting general Bougenel78) he was invited to the emperor’s annual birthday festivities at Compiègne in December.

The cumulative work weakened his health, and by 1863 he sought recovery in his beloved Rome for dizziness, rheumatism, and failing eyesight.

He rejoiced at meeting the Holy Father in the Vatican on 6 December 1863, and a commission to paint a portrait of Pope Pius IX seemed imminent.

Also a music lover, he visited Liszt50b in Rome, and wrote to his brother on 17 February 1864: “Litz [sic] was very kind to us and played music for us, which is now (it seems) very rare. He was prodigious.”

Two weeks later his wife contracted smallpox; Hippolyte initially avoided contagion but succumbed to the disease in mid-March and died on 21 March at the age of fifty-five. In addition to his religious murals, he created over ninety portraits. The drawing of his youngest son, Paul-Hippolyte, remained unfinished.