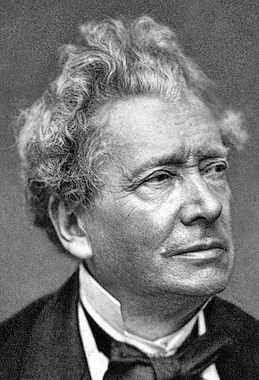

Joseph Isidore Samson (1793 – 1871), actor, teacher, dramatist

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: by Villeneuve (1853); 3rd: litho Aubert (1820); 4th: anon. (c.1830); 5th: by Carjat (1860). Images 2 & 4 reversed to correct his skin lipoma position.

Actor, professor, and playwright Joseph Isidore Samson is depicted opposite his friend and colleague Régnier77, perhaps discussing theatrical highlights during their visit to de Nieuwerkerke’s16 vendredi-soirée in March 1852. These may have included Samson’s and Régnier’s immensely successful performances in Mademoiselle de la Seiglière (by Jules Sandeau and Régnier) from 4 November 1851 (with interludes by composer Offenbach), or the premiere on 19 February of Augier’s53 Diane, featuring Rachel and Régnier.

Samson, who began his career in Rouen, joined the Odéon theatre in Paris in 1819 and the Comédie-Française (Théâtre-Français) in 1826, often undertaking two roles in a single evening to secure a living. He was appointed professor of drama and declamation at the Conservatoire in 1829. In the revolutionary year of 1830 the government-run Comédie-Française, threatened with suspension and providing insufficient income, led him to move to the commercial theatre of the Palais-Royal. The constitutional monarchy of Louis-Philippe, however, regarded the Théâtre-Français as essential to public education and entertainment, and the court ordered Samson to fulfill his contract.

caricature by Lhéritier (1831)

Writer and journalist Eugène de Mirecourt praised Samson’s stage work:

“By turns serious and comic, his talent possesses a thousand delicate nuances, a thousand hidden resources; he knows all the possibilities of the art. He identifies with the character and, as it were, melts his soul into his roles, to more surely imbue a character with the stamp of truth, the prestige of beauty, the force of nature.”

Samson’s roles as actor, as an executive of the Association of Dramatic Artists (founded by the influential baron Taylor, his lifelong friend and patron since their boarding-school days in Belleville), and as professor at the Conservatoire made him a focal point for female students aspiring to the theatrical profession. At the time, the only law permitting secondary education for girls dated from October 1815 and allowed students of both sexes to be admitted to the school of the Théâtre-Français.

Samson became famous as the discoverer of Mademoiselle Rachel Félix81. In his Mémoires (1888) he recounts that one of his students (Rey, in 1834) led him to judge a young actress (aged fourteen) at an obscure theatre on the Rue Saint-Martin and that he was astonished by her performance. He offered to give her private lessons free of charge. In February 1838 he arranged for his pupil to join the Comédie-Française and delighted in teaching her. He writes: “I will never forget [the magnificent evening performances], nor those mornings devoted to the dramatic instruction of my marvelous pupil. I count them among the most beautiful hours of my life.”

When the king attended a performance of Rachel in Cinna (by Corneille) at the Théâtre-Français on 27 October 1838, he intended to leave but asked director Védel: “Isn't the play you're next going to perform by Mr. Samson?” “Yes, Sire,” replied Védel. “Well! Since I was so pleased with the pupil I will stay to see the comedy of the master.” The subsequent play by Samson may have disappointed him.

Despite frequent quarrels, Rachel continued to rely on Samson to help her understand and interpret her roles; the few plays she rehearsed without his assistance were unsuccessful. This makes Samson’s presence at Rachel’s vendredi-soirée performances highly plausible.

Their close professional relationship ended in 1853, when Rachel refused to play at Samson’s benefit performance; Samson’s favorite student, Sylvanie Plessy, who returned from St. Petersburg for the occasion, then took her parts.

Over many years at the Comédie-Française, Samson instructed hundreds of students, primarily young women who were often described by the press as attractive. Principal names include Sylvanie Plessy (whom he regarded as a member of his family), Madeleine and Augustine Brohan, Stella Colas, Léocadie Doze, Nathalie Martel, and Rose Chéri. He briefly tutored Sarah Bernhardt, though he did not inspire her.

As early as 1841 the press (L’Indépendant) observed that Samson’s role as teacher presented a conflict of interest with his positions as committee member of the Association, as societaire (shareholder approved by the Ministry of Culture), and as actor at the Comédie-Française. Critics pointed to a sequence of mediocre comedies —such as Samson’s deplored La Belle-mère et le Gendre (The Stepmother and the Son-in-Law, 1828)— which seemed to promote the talents of Samson’s students rather than to showcase masterpieces by Corneille or Racine.

They noted that accomplished societaires like Régnier often yielded to Samson’s opinions on repertoire. De la Boullaye of L’Independant recommended entrusting the education of a new generation to distinguished retired actors and suggested that Samson abandon teaching to concentrate on acting. It was not until 1854 that Samson was relieved of his Conservatoire chair and Régnier appointed as his successor. Samson, however, continued private teaching for many years and did not formally retire from the stage until 1863.

Like others in Une Soirée such as Auber56, Penguilly57, Duban60, and Morel-Fatio63, Samson was affected by the war of 1870. He left Paris for Blois at the outbreak of hostilities (as Duban had done) and returned in March 1871 to visit his son, daughter, and grandsons. He endured a harrowing journey, delayed for hours by Prussian troops and forced to walk the final stretch in the cold, only to find that the Commune of Paris had been proclaimed. The cold and the shock of the Commune revived memories of the horrors of his early childhood and of 1815, further undermining his health. He died on 28 March 1871.

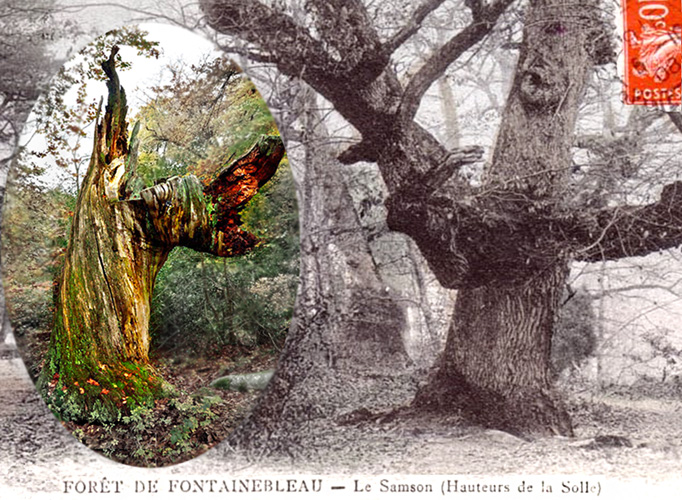

None of his plays have been performed after 1860. Samson's only lasting memory is an oak tree Le Samson at the Fontainebleau forest, where its (dead) trunk still remains today.