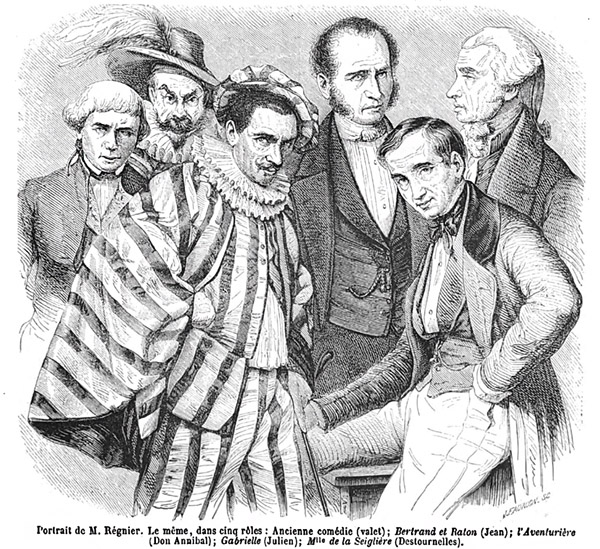

Philoclès Régnier (1807–1885), actor of the Comédie-Française

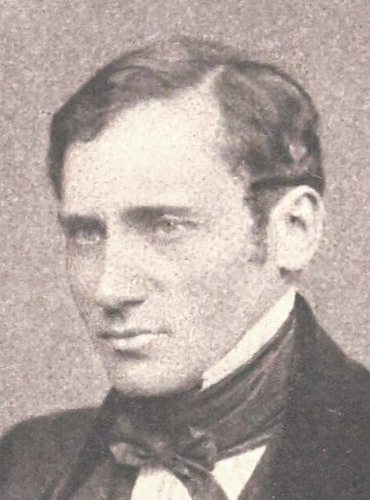

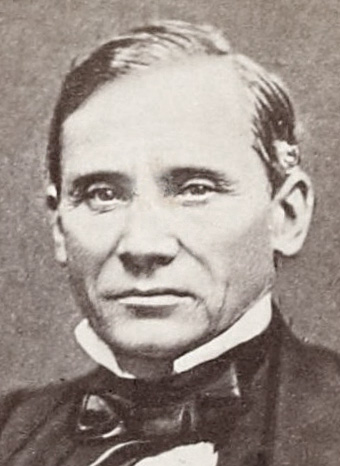

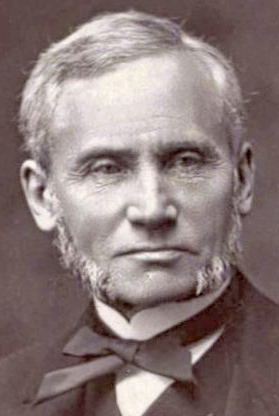

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: by Villeneuve (1849); 3rd: album Figaro (1853); 4th: by Brandonneau (c.1870); 5th: by Chartran, with Chevalier rosette (1872);

Philoclès François-Joseph Régnier de la Brière appears in Une Soirée seated in the second row, at the right-hand “theatre” section, alongside Samson80 and behind Meyerbeer76 and Scribe74. In this group he is engaged in animated discussion with the painters Isabey75 and Flandrin79. Both Régnier and Samson were leading sociétaires (company share owners approved by the Ministry of Culture) of the Comédie-Française and frequently performed with the tragedienne Rachel Félix81, a recurring guest at de Nieuwerkerke’s16 soirées.

Facial features and their reproduction in Dayot’s engraving support the identification of Régnier. Unlike musicians who were regular invitees, actors typically received fewer invitations, often timed to coincide with a recent theatrical success. The absence of caricatures of Régnier by Eugène Giraud11 is consistent with such episodic attendance. The most probable occasions for Régnier’s presence correspond to the sustained success of Adrienne Lecouvreur (premiered 14 April 1849), in which Rachel, Régnier, and Samson performed, and to later popular productions in which Régnier starred, such as Augier’s53 Gabrielle (29 January 1851) and Diane (19 February 1852).

Rachel’s documented appearances on 5 and 19 March 1852 offer particularly plausible dates for Régnier’s attendance and may have shaped de Nieuwerkerke’s (or Biard’s36) compositional decision to concentrate a theatrical vignette in a hemicycle around her figure, a scheme revised after 1854 in light of Rachel’s private affairs. Besides Regnier, the presence of Rachel would also be a reason for her circle of friends Augier, de Musset73, Samson, and Ponsard70a —all of whom had, or aspired to, intimate relations with this famous tragedienne— to attend.

by Lorsay (c.1860), after

photo by Villeneuve (1849)

Aptly named Philoclès (friend of glory in Greek) by his godfather, Régnier followed a theatrical lineage: his mother, Charlotte Tousez de La Brière, was a comédienne. After a first appearance on stage at age four, Régnier resolved to pursue the profession of actor. His mother, however, opposed this path and sent him to study painting at art school; he soon abandoned those studies to enrol in architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts.

Finding neither interest nor success in architecture, he turned to the practical theatre: he accepted small parts in Montmartre productions and, despite the absence of formal acting training, attracted the attention of provincial managers. He was engaged successively by companies in Metz and Nantes, and in 1831 returned to Paris, where his portrayal of Figaro at the Comédie-Française secured his reputation.

Appointed sociétaire in 1835, Régnier became one of the company’s influential actors responsible for selecting, adapting, staging, and performing repertory at the Théâtre-Français.

He played a formative role in shaping new comedies: initial sketches were honed through iterative rehearsals to heighten comic effects, a process in which Régnier’s instincts for pace, timing, and audience response were decisive.

Contemporaries credited him with an unrivalled command of Molière’s repertory and with an ability to secure box-office success; Arsène Houssaye (one of de Nieuwerkerke's best friends) described him as “the master who had learned from the masters.” It was common for colleagues to seek his advice on role preparation, and mentioning “I consulted Regnier” was often decisive in effecting stage alterations.

It was thanks to Régnier's efforts that a Molière fountain (with Visconti09 as architect and statues by Pradier03) was installed in 1844 across the street where this great playwright had lived.

In a letter from 1855, Charles Dickens recalls the loge that Régnier arranged for him, and is full of praise of the actors, wondering why none of the English actors had this sacred fire. At the same time he is appalled by the Theatre-Francais building, “a chilling environment like a vast tomb […] where one goes to meditate on dead friends or thwarted loves.”

Alfred de Musset observed Régnier’s sacred fire in August 1849: shortly after the actor’s fourteen-year-old daughter Cécile died of typhoid fever, Régnier nonetheless continued to provoke uproarious laughter from audiences in Augier’s Gabrielle. De Musset expressed his sympathy in a sonnet addressed to the bereaved actor in the Poésies Nouvelles published in the Revue des Deux Mondes; Augier composed a consolatory poem for Régnier in 1850.

Critics acknowledged limitations in Régnier’s physique and voice relative to some peers, yet consistently praised his tenacity, inventive comic intelligence, and theatrical verve. His steadiness in family life and his reputed gallantry contrasted with the more turbulent private lives of many of his contemporaries, making him a natural instructor and mediator among actors.

In 1854 Régnier joined the faculty of the Conservatoire de Paris and, on retiring in 1872, received the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. He continued to work as a stage director at the Opéra Garnier into his late seventies and remained a sought-after consultant: directors regularly solicited his professional appraisal before mounting new plays. Contemporary testimony suggests that a large majority of Parisian comic actors regarded Régnier as their principal pedagogical authority.