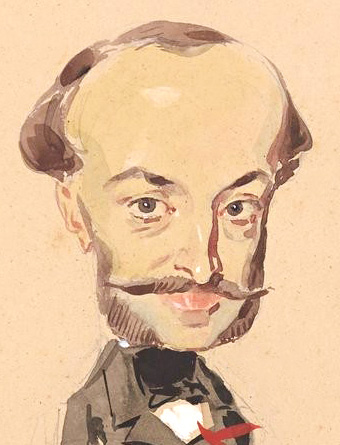

Frédéric Villot (1809 – 1875), art historian, conservator, administrator

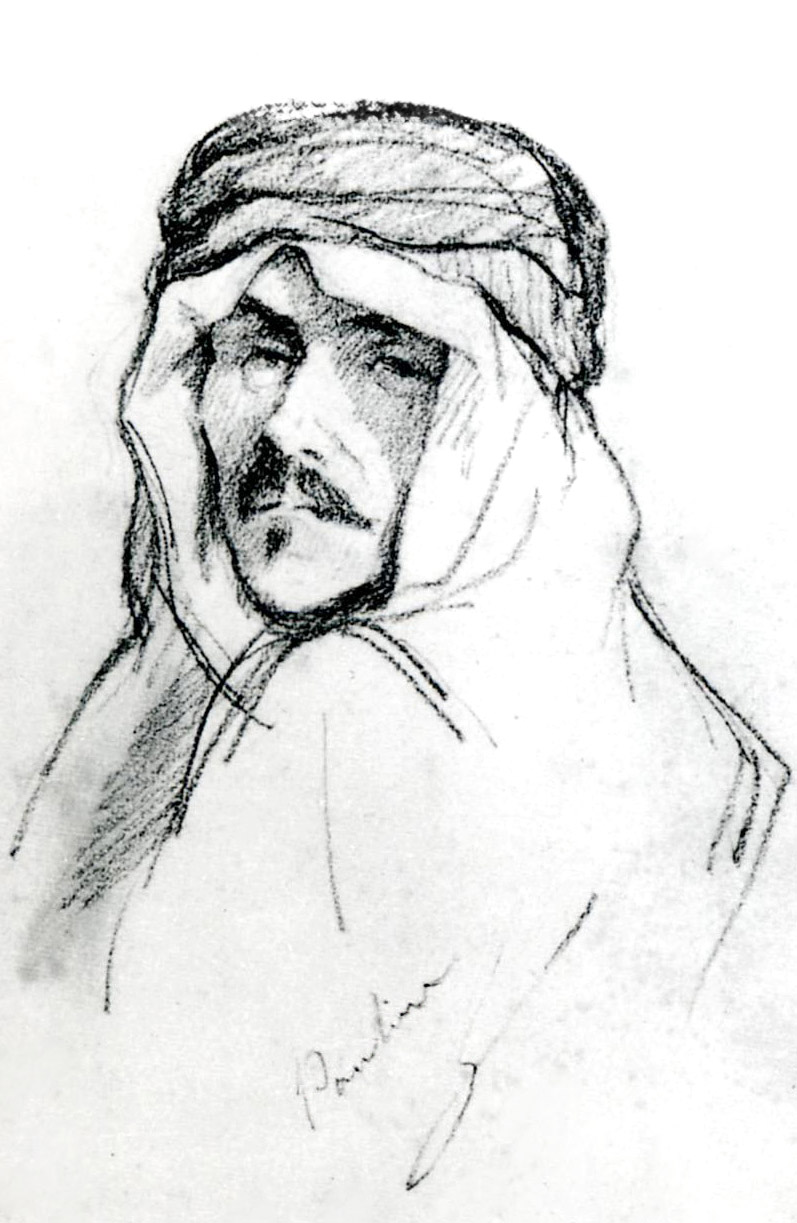

1st image: Soirée; 2nd: by Rodakowski (1854); 3rd: by Giraud (c.1860); 4th: by Delacroix (1832).

Director-general Count de Nieuwerkerke16 possessed artistic vision, charisma, and an imperial-level network. What he lacked —and did not aspire to— were the practical tasks of operating and maintaining museums. For this he assembled an elite group of collaborators. With Viel-Castel43, Morel-Fatio63, and Reiset65 present in Une Soirée, their supervisor Frédéric Villot, although not identified in Dayot’s engraving (1900), had to be there as well. Both Eugène Giraud’s11 caricature and a painting of 1854 by Henri Rodakowski —judged by Delacroix a poor likeness— correspond to Marie Joseph Frédéric Villot, head of the Louvre’s paintings department. His presence is confirmed for 28 March 1851 and 10 December 1852, but as conservator he was expected to attend many such evenings.

by Eugène Giraud (c.1860)

Combining the qualities of art historian and natural bureaucrat, with a distinguished family background and a marriage to Pauline Barbier, the coquettish daughter of a baron, Villot was precisely the figure de Nieuwerkerke required.

Art inspector Chennevières20 wrote in his memoirs:

“In my life, I have never encountered a more self-centered, more naively selfish, more forgetful of others, yet also more harmless personality than that of poor Villot. […] He had done everything, invented everything, written everything, and knew everything.”

At the Louvre, Villot was pivotal in establishing and publishing catalogues of the museum’s paintings, finally enabling the public to learn more about the works and their creators. He collaborated with Clément de Ris26b to improve the selection for the annual Salons (of which he often was a jury member), grouped scattered works of single masters, and was instrumental in acquiring major Flemish and Italian masterpieces from the King of Holland in 1850.

Born in Liège, the elegant socialite Villot claimed descent from actress Adrienne Lecouvreur and Maurice de Saxe, marshal general of France, thereby asserting a family tie with writer George Sand. The first claim was true: through his maternal line he was connected to Adrienne’s daughter Françoise Couvreur (1714–1768). The second was false: at the time of Françoise’s birth in Strasbourg, Maurice de Saxe was only seventeen and serving in the Saxon army. He and Adrienne did, however, have a passionate relationship in the 1720s, ending with her suspicious death.

Dramatists Scribe74 and Legouvé used this romance for a five-act play that achieved spectacular success at the Théâtre-Français when Une Soirée was conceived, starring actors Rachel81, Régnier77, and Samson80. This explains Villot’s placement beside them.

Despite anecdotal ties, George Sand and Pauline Villot adopted each other as cousins and became lifelong friends.

Villot lived at Champrosay, along the Seine southeast of Paris.

He met painter Delacroix10 when he bought his work Murder of the Bishop of Liège (Villot's town of birth)(1829), and they became close friends.

Is it coincidence that Villot and Delacroix appear to look directly at each other across the salon of Une Soirée?

Champrosay was Delacroix’s favorite place to stay and sketch. His journal reveals his affection for Pauline, which was mutual, and probably began soon after Villot introduced her to Delacroix after their marriage in May 1831. She was kept updated of his whereabouts on his trip to Morocco in 1832.

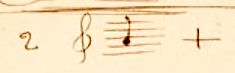

Delacroix created several portraits of Pauline, and she served as model for other works. In 1833 they sketched each other in Arab costume.

Romantics note Delacroix' cryptic signature "2 la [music note] + " (Deux la croix) under his drawing, with Pauline signing her name at the place of Delacroix’s heart.

While Delacroix spent time très amicalement with Pauline, her husband was in Venice recovering from cholera and studying Italian masters Veronese and Tintoretto. In 1844, Delacroix started to rent a cabin nearby Villot, which he later bought. Over the years, the infatuation from their youth changed into a lasting friendship. Delacroix' journals contain more references to Villot and his wife than any other friend.

Villot was also an erudite music-lover, pursuing music study and composition before he became conservator. Jules Pasdeloup12, pianist and composer responsible for musical events at de Nieuwerkerke’s vendredi-soirées, dedicated his second quartet for two violins to him. An accidental meeting with Richard Wagner led to a friendship in which Villot undertook the French translation of Wagner’s operas. Music historians relish Wagner’s letter Zukunftsmusik (“Music of the Future,” 1860) to Villot, in which he described his evolving views on opera composition.

Villot introduced the young Camille Saint-Saëns —whom he had asked to play Wagner’s music for him— to the composer. On 13 March 1861 Wagner’s Tannhäuser, sponsored by minister Fould17, premiered for a conservative audience accustomed to Meyerbeer’s pompous operas and proved a disaster.

Villot’s confidence in his competence and his desire to restore the darkened surfaces of his beloved Veronese and Rubens’ led him to remove their varnish, thereby unfortunately eliminating embedded paint and destroying their luster.

The press was merciless, accusing him of by "Villotining" these artwork of having fatally damaged several Titians and having killed Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana.

Viel-Castel wrote: “When Villot decides on restorations, they are carried out with the same carelessness as the laundry of the Invalides.”

The Chronique des Arts declared: “He did to these paintings what Viollet-le-Duc did to Notre-Dame” —Viollet-le-Duc40a being notorious for “restoring buildings to a state that never existed.”

When Delacroix discovered that Villot had treated his Massacre at Chios (1824) in the same way without informing him, he insisted that artists must always retain the right to retouch their own works.

Following the negative publicity for himself and for the Louvre, Villot was forced to resign in 1861. Fellow conservator Reiset succeeded him. De Nieuwerkerke came to his aid by "promoting" him to a powerless position as secretary-general, overseeing budget plans until failing health compelled him to stop. He died in March 1875, one month after Pauline.